Month: August 2015

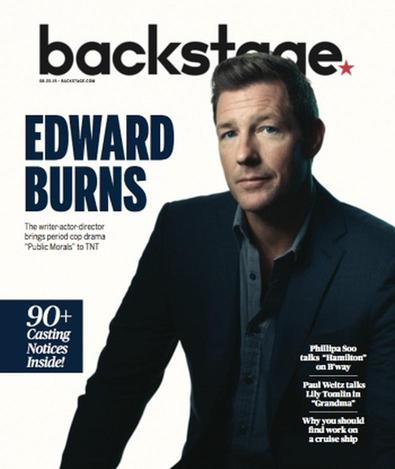

Edward Burns ventures into ’60s New York in Public Morals trailer

‘Public Morals’ Trailer: Edward Burns’ Period Cop Drama Targets The Underbelly Of The Vice World

Fast chat: Edward Burns on his new TNT series, ‘Public Morals’

Edward Burns Celebrates TNT’s ‘Public Morals’ After 18 Years in the Making

Interview: Edward Burns writes what he knows (and loves) in TNT’s Public Morals

A Watershed Year for Edward Burns

For ‘Public Morals,’ Edward Burns Exhumes the ’60s From Manhattan Streets

Unearthing signs of the ’60s in New York

NEW YORK — Tourists walking in New York look up at the skyscrapers and blinding billboards. Locals look down to avoid stepping in gum or whatever. Edward Burns lately has been looking here, there and everywhere when he strolls the city: at stoops, windows, cornices, railings. He has been looking for the 1960s.

Burns, an actor, director and writer who first came to prominence in 1995 with the Sundance prizewinning movie “The Brothers McMullen,” is bringing his indie-film sensibilities to television with a new series called “Public Morals.” Shot entirely in New York, it is a cop-and-gangster tale set in the early 1960s. That has had Burns keeping an eye out for places in the fast-changing city that still look more or less as they did a half-century ago.

“Once I started writing the script,” said Burns, who is writer, director and a star of the series, “I would just walk around the city with my phone, taking pictures of any old building I could find that hadn’t been power-washed, that still had the wooden front doors and wooden window frames and the old wrought-iron gates. Old sidewalks. Cobblestone streets. Anything like that that I could find.”

The series has its premiere Aug. 25 on TNT, and it’s a leap for the network, which recently has been trying to broaden its original programming. The show focuses on a squad in the New York Police Department that deals with vice crimes — gambling, prostitution — and its alliances and clashes with an Irish-American gangster family.

Worlds away from a murder-per-episode police procedural, it is thick with characters living in a morally gray zone, calling to mind shows like “The Shield” and “The Wire.” Burns’ character, a cop named Muldoon, is related through an uncle to the gangster operation, and he and the rest of the officers work a balancing act in which they sometimes enforce the law and sometimes take bribes not to enforce it. It’s an atmospheric treatment that asks viewers to invest in interweaving storylines spun out slowly, and for Burns that meant casting a lot of New York actors and sending them out on the street.

“It was very important to us that this was a ‘real’ New York show,” he said. “I’ve said for years that the best co-star an actor can have is a New York street corner, and we did not want a show that took place entirely on a soundstage.”

Despite all those glass skyscrapers, capturing an early ’60s look wasn’t as hard as you might think, Burns said.

“If you put a bunch of old cars on the street and dress your extras up in the period clothes, there are still blocks and blocks that pretty much look the same,” he said. “We’ll go in digitally afterwards and maybe have to erase some air conditioners or a more modern sign or the blinking hand instead of ‘Don’t Walk’ and ‘Walk,’ but there’s enough.”

There’s enough, but sometimes you have to move quickly. Giving a walking tour of locations the show used in Tribeca, Burns pointed out a vacant lot at Desbrosses and Washington streets that until recently held an imposing if somewhat neglected-looking eight-story building with the look of old New York. Hearing that the structure was about to be demolished, he hurried a crew over, stuck one of his actors, Keith Nobbs, in a phone booth outside it and shot a scene that turns up in episode seven. “We got to it about two weeks before it was torn down,” Burns said.

“Public Morals” is aiming for a particular time period, but what it is not aiming for, Burns said, is a lot of specific references in the style of “Mad Men.” “We’re never going to identify what year, or even what time of year,” he said. “I didn’t want it to be a show about the ’60s and have it go from event to event.”

Instead, he said, he took a lesson from old Westerns that he loves. “With a lot of those films, you never had a sense of, ‘Oh, this is 1880s Old West, as opposed to 1850s Old West,’” he said.

His character is a sort of linchpin who keeps both officers and gangsters in line but who also has a home life that includes a son with disciplinary problems at school. Michael Rapaport plays a fellow officer who falls into an odd interdependent relationship with a call girl. Brian Dennehy, as the godfather of the gangsters, has a simmering coup to keep an eye on, as well as a volatile son (Neal McDonough) with strong ambitions.

Although he was born in 1968, after the show is set, Burns has drawn on personal connections to create the series. His father and an uncle are both retired New York police officers, and his father, he said, “really helped me with a better understanding of what the relationships were like within the Police Department — how might the captain treat the new kid who shows up at the office, what those exchanges might be like.”

Oh, and the gangland side of “Public Morals” might also be represented in his gene pool. At his office in Tribeca, Burns pulled out some old family photographs of a great-grandfather, on his roof in Hell’s Kitchen apparently preparing a pit bull for dogfighting.

Q&A Ed Burns displays his original indie attitude with ‘Public Morals’

Ed Burns broke into the public consciousness 20 years ago when he wrote, directed, produced and costarred in “The Brothers McMullen,” an independent film comedy about Irish Americans in New York. Since then he has appeared in numerous other films, including “She’s the One,” “27 Dresses” and most notably “Saving Private Ryan.”

This fall the 47-year-old New York native is back with “Public Morals,” a TNT period drama about the NYPD vice squad that he wrote, directed and stars in. He spoke with The Times by phone from New York:

“Public Morals” is about the NYPD in the 1960s when, according to the show, cops took bribes and consorted with hookers. Your dad was actually a sergeant on the force then — what does he say about all this?

My dad is the one who turned me on to my love of New York and NYPD history. We’re constantly finding these great old books and sharing them with one another. There’s a book from I think the ‘30s or ‘40s called “A Cop Remembers,” about a cop in New York at the turn of the century. They talk about institutionalized corruption. There isn’t a book that you can pick up that doesn’t talk matter of factly about the way things used to be. The reason I set this show in the early ‘60s is that that was the last era that that was taking place. As you moved into the late ‘60s and the ‘70s, not only had the city changed, but the police department had changed pretty dramatically.

In a perfect world we get to play with five or six seasons and we can see how that institutionalized corruption was sort of exposed and then ended.

This isn’t just another cop show. For one thing, it’s not set in the homicide division. The character you play, Det. Muldoon, puts the heat on prostitutes and gamblers, not murderers.

We’re very lucky that TNT really wanted to move the network in a different direction. Part of that was more character-based storytelling rather than episodic, murder-of-the-week storytelling. There was never a conversation about “How do we make this a procedural?” They jumped right in and were fully supportive. I think that’s why you’re seeing a lot of indie filmmakers making the jump to TV. “Why bang my head against the wall with the movie studios who only seem to be interested right now in fantasy?” You look at David Simon, David Chase, Matthew Weiner — the great success the networks are having when they embrace the filmmakers’ individual voice and, most importantly, leave them alone.

Earlier this year you published a book, “Independent Ed,” designed as a primer for the aspiring young filmmaker. What’s easier to write, a screenplay or a book?

Unlike writing a screenplay, I found writing the book, beyond the first draft, was like a homework assignment. Going back and talking about the individual films was a lot of fun. It reminded me of some things and anecdotes that I had forgotten. But then going through the transcript and having to sort of fine tune it and put it into my voice, that was really the challenge.

The greatest thing happened this past weekend. Out in the Hamptons they do this author’s book fair. About the fifth woman in line comes up with a book and she says, “Do you recognize me?” And I say, “I kind of do, give me a hint.” She says, “You were in high school…” I say, “Oh, my God, Mrs. Maxwell! … Do me a favor and open up the table of contents.” You know, my first chapter is “Thank you, Mrs. Maxwell.” She was the teacher who gave me the kick in the butt and believed in me as a writer.

Is there even an indie film market that young people can still aspire to? Everything today seems like it’s big-budget franchise pictures.

Absolutely. Every year there is another filmmaker who shows up at Sundance with a lower-budgeted movie, and that kid ends up with a career. Just this past year, I haven’t seen the film, but apparently there was a feature film that was shot on an iPhone at Sundance.

It’s evolved in the last 20 years since “Brothers McMullen,” but if anything it’s easier for kids today because the barrier for entry is almost nonexistent. You can get your hands on a digital camera, in this case an iPhone, and you can edit on your laptop and you’ve got yourself a feature film. Back when me and guys like Richard Linklater were starting with our low-budget films you had to find somebody who actually knew how to shoot films and you had to find a film camera, and then film stock and film processing, all of which is very expensive.

So If you were making “Brothers McMullen” today you’d be shooting it on an iPhone?

I don’t know about an iPhone, but I absolutely would not be shooting it on recanned 16-millimeter film stock.

Your wife, the former supermodel Christy Turlington, is also a filmmaker; her documentaries “No Woman, No Cry” and “Every Mother Counts” are about making pregnancy safer for women in developing countries. Have you had advice for her?

In the editing room I would just say, “You have to remember, you also need to tell the story along with the message that you’re trying to get out. You’re trying to bring awareness to maternal mortality. OK, but you’re still going to have an audience sit down here for 90 minutes — so you have to find the story within all that footage.”

You’ve been very candid about your failures as well as your successes. After “Saving Private Ryan,” it looked as if you might become a huge movie star. Why didn’t that happen?

After “Brothers McMullen” my goal was to write and direct and act in one movie a year and stay in New York. When trying to get my third film financed, my agents came to me: “Look, if you’re going to continue to cast yourself please think about acting in someone else’s film in a studio film. You will become more famous, and it will then be that much easier for us to put together the financing for the films you want to make as a filmmaker.”

I looked at a bunch of scripts and one of the first scripts I get is for “Saving Private Ryan.” I threw my hat into the ring and couple of months later we got the call that Spielberg thought I was right for the part. After “Private Ryan,” my agents were then like, “OK, you’ve got a big part in a big Steven Spielberg movie; forget about making indie movies, it is time to pursue being a movie star.”

At the time, I was all in. I was ready to do it. I moved to L.A.; we read a ton of scripts, a lot of offers were coming in. I waited almost a year before we found what we thought was the right follow up, a movie called “15 Minutes,” where I’m co-starring with Robert De Niro.

It felt like a no brainer. But then “15 Minutes” came out and kind of did not do too well, so the movie star thing was already starting to fizzle. I got to do a movie with Angelina Jolie, a romantic comedy called “Life Or Something Like It.” That bombed. I did a movie that I really loved called “Confidence” with Dustin Hoffman and Andy Garcia and that bombed. So that was sort of the end of the run where people were calling me up saying, “Hey, we want you to be the lead in our movie.”

Young people who see “Public Morals” may be struck by some of the unfamiliar parenting styles on display. For instance, in the first episode Muldoon is seen berating his school-age son with a sarcastic monologue about what an idiot he has raised.

The one part of the show that is autobiographical is the relationship between the oldest son and Muldoon. That scene that you mentioned is word-for-word me and my dad when I’m in the sixth grade.

But that’s not how you talk to your kids?

No, no. Those days are over. But back in the ‘70s, that’s the way we were raised.

Edward Burns is arresting in ‘Public Morals’

What Mad Men did for smokey, sexy advertising, Public Morals aspires to accomplish for cops, gangsters and molls.

The period police drama is the brainchild of New York native Edward Burns, who was born in Woodside, Queens, and lives in downtown Manhattan with his wife, model Christy Turlington, and their kids Grace, 11, and Finn, 9.

So it makes sense that when he set out to create, write, direct and star in a new series, it was all about the city he calls “my other baby.” In TNT’s Public Morals, premiering Tuesday (10 p.m. ET/PT), he’s a cop (and a dad) with a loose ethics code. The main rule of Terry Muldoon, the plainclothes cop played by Burns: “You do not draw attention to yourself.”

For Burns, the show, set in the ’60s, is all about authenticity. “I wanted New Yorkers to look at it and think, ‘That’s the way the city used to be, and the way it used to sound.’ I tried to cast only born-and-bred New York actors. A New York accent is tricky to pull off. We have retired cops on the show. They have the walk, the cadence and the delivery,” he says.

Burns broke through as the director and star of 1995’s The Brothers McMullen, which took place mostly in his Long Island hometown of Valley Stream and dealt with the relationships of three Irish-Catholic brothers. Since then, his career has been something of a mixed bag, but Public Morals is a passion project he’s been nursing since 1998. He’d long wanted to create an homage to old New York, coupled with a look at police and gangster life at the time.

“I recognized that the audience that used to love independent filmmaking and storytelling, that audience was no longer going to the theater but getting that type of storytelling via TV. You have support for your vision, creative control and a real budget. I went home and dusted off the old scripts,” he says. “I always wanted to do a period cop movie and a period Hell’s Kitchen gangster story,” he says, referring to a West Side neighborhood.

Why, you might wonder? It all goes back to Burns’ family.

“My father and my uncle were both retired city cops,” he says. “You hear all these grand old stories about what the city was like in the ‘50s and ‘60s. I wanted to make a show about guys like that. We couldn’t get it made and I put it on the shelf. It’s been one of my passion projects. I became obsessed with Hell’s Kitchen and Irish history in New York. I wrote four scripts about Irish gangsters, (but) all of those films I could not get made.”

Enter TNT, which offered Burns full creative control.

“When we sat down to discuss the look of the show, we didn’t want it to look like a TV show. We’re filmmakers. Let’s make a 10-hour movie,” he says.

On the show, Burns is a foul-mouthed paterfamilias, who berates his eldest son for being a cut-up in class and embarrassing his family with his asinine antics. Burns in real life is nothing like him, but there are other family connections.

“The older son, James, the scenes that involve him and what it was like to grow up in a house where your father was a tough cop, that’s me and my dad when I’m in the 7th grade,” he says. “That was pretty surreal for me to playing a version of my dad, going old school on my son. In my life, I’m nothing like that.”

Ed Burns’ real-life cop father inspired his new police drama

Ed Burns’ new crime drama, “Public Morals,” is a gritty valentine to his police-sergeant father.

Growing up on Long Island and in Queens, Burns was regaled by his father, Edward J. Burns, with stories of his cop exploits. Many of dad’s stories have found their way into the show, which premieres Tuesday at 10 p.m. on TNT.

Burns directs and stars as Terry Muldoon, head of the Public Morals Division, a plainclothes unit of the NYPD specializing in “victimless crimes.” He supervises a tightknit band of officers who crack down on everything from prostitution to illegal craps games.

The actor’s 78-year-old father, who lives on Long Island, served as both inspiration and informal adviser. Muldoon even has the same badge number — 5425 — as the elder Burns did.

“He helped me with the interoffice dynamics,” says the actor-director. “What would the relationship between the captain and the lieutenant be like, what would they share with one another?”

On the vice squad, his father explained that “you didn’t want anyone to know you were a police officer. [You] didn’t have lights on the cars. Or radios in the cars. [You] dressed a certain way to fit in.”

In one episode, Muldoon and his crew arrest some prostitutes, and then take them to grab something to eat. It’s a story drawn straight from the senior Burns.

“If [they] arrested these girls after night court had closed, they’d be sitting all night in jail, so the cops would take the girls out for hot dogs and sandwiches as a courtesy,” says Burns, 47.

Such scenes make being a cop in the ’60s look like a pretty good time, and indeed, “Public Morals” has a lighter tone than the usual brooding, soul-searching Hollywood portrayals of New York police life, like Sidney Lumet’s “Serpico.”

Burns recalls a story that one of his dad’s cop buddies shared. “They got involved in a shootout and they were chasing the guy across several rooftops, and the partner says to my dad’s friend, ‘Can you believe they pay us to do this?’ That’s something I wanted to get across.”

As part of his research for the show, Burns pored over his dad’s arrest records.

“I combed through those to get some sense of what areas had heavy traffic. There wasn’t a street corner in Manhattan where there wasn’t an arrest,” he says. “And nobody gave you their real name.” He mentions one as an example of how silly the game could get: “Cricket Davenport.”

While the main plot of the show concerns Muldoon’s attempts to control the activities of the West Side’s Irish mob, run by Joe Patton (Brian Dennehy), the show also explores what Burns calls “the dynamics of Irish families and the boisterous way we communicate with each other.”

It’s a subject he first tackled in his 1995 hit independent film “The Brothers McMullen,” about three Irish-Catholic brothers on Long Island.

In the new show, there’s a scene drawn straight from Burns’ childhood. Muldoon gives his eldest son, James (Cormac Cullinane), a lecture after he gets in trouble in class with a ball-busting teacher named Sister Paul Eugene (Samantha Buck).

“It is your job to interrupt the class with your asinine jokes,” Muldoon scolds the boy sarcastically. “And that just makes me so proud.”

“That scene is word-for-word from my childhood,” says Burns, who grew up the oldest of two siblings. “You remember getting yelled at . . . That sarcasm was my kitchen.”

Burns shares his own kitchen with his wife of 12 years, supermodel Christy Turlington. They live in Tribeca with their two children, Grace, 12, and Finn, 9. The director’s love affair with the neighborhood began when he was editing his 1996 film, “She’s the One,” on Worth Street, and he hung out at Walker’s, a bar on North Moore Street (which also hosted the premiere party for “Public Morals”).

“I fell in love with how quiet the neighborhood was,” he says. “We’ve been there since 1999. It’s family-centric.”

He attributes the success of his marriage to the fact that both he and Turlingtonare “very close” with their families and have remained in the city.

“We both stayed in New York,” Burns says. “That keeps you in check.”

Edward Burns Explains How Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg and ‘Game of Thrones’ Influenced His (Great) First TV Series, ‘Public Morals

For the last decade or so, you probably know Edward Burns as one of two people: The first is that charming New Yorkah who pops up in romantic comedies like “The Holiday,” “27 Dresses,” “Friends With Kids” and even “Will & Grace.” He’s snagged a few roles as cops in a couple of studio flicks, as well, but he’s a tried and true “Prince Charming”-type for anyone who loves a thick Queens accent. That person, though, is Edward Burns, Studio Actor. Far more interesting to the indie community and film fans at large is Edward Burns, Writer, Actor, Producer and Director.

Since his debut film, “The Brothers McMullen,” took home the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival in 1995, Burns hasn’t stopped writing — and directing, and producing, and acting and more. He’s been pumping out character-driven indie films for two decades now, and helping push VOD distribution into the mainstream along the way. An innovative and inspired filmmaker, Burns — like so many others — has now taken his talents to the small screen. But he’s not done pushing boundaries just yet.

“Public Morals,” a 1960s gangster saga focusing on both sides of the law, is set to become the first TNT drama to stream new episodes online before airing them traditionally. One day after the series’ premiere on August 22, the first four episodes of the 10-episode first season will be made available on VOD, TNT’s website and other outlets to bring as much exposure as possible to the exciting new drama. Not only that, but Burns wrote and directed every episode of “Public Morals,” making the series a more filmic and auteur-driven effort, a la “True Detective” Season 1 or “The Knick.” Ahead of his show’s premiere, Burns spoke with Indiewire about his personal connection to the material, why he made the transition from indie film to TV, how Steven Spielberg — his director on “Saving Private Ryan” — helped with the show and whether or not he plans to return to the indie film world anytime soon.

You’ve been trying for a while to get this Irish cops and gangsters project going, and you grew up in a family of cops, right? So this is pretty personal?

Yes. The stuff in it that’s autobiographical is limited to the relationship between Terry Muldoon and his sons. The other story we’re seeing — the subplot in the pilot — is word-for-word me and my dad when I’m in the sixth grade. And there are other moments like that between my character, Terry, and his son James, that pull from what it was like to grow up with a father who was a police officer; what it was like to grow up in that culture and climate in a big cop family where a lot of your social life — weddings, funerals — were attended mostly by cops and their families. All the other stuff, the cops and the gangsters come from, probably, 20 or 25 years of my obsessions. The movies I loved, the novels I tended to read, and the nonfiction that I was obsessed with, [it] always had to do with New York City, Hell’s Kitchen, gangsters, cops, the waterfront, Times Square, those kinds of things. I took all of those obsessions and put it into the show.

I’ll even go one step further: The show was born after I wrapped “Mob City.” Bugsy Siegel, the character I played, got killed off, and the guys at TNT wanted to know if I had any interest in developing or creating a television show. And at that point, I didn’t. I thought about it, but I didn’t really have any ideas for a TV show. So I went back home to New York, and I said, “Why don’t I come back to LA in the fall and see if I can pitch you something?” So when I came home, I looked at the stacks of unproduced screenplays that I had in my office. I kinda had two genes that I had been playing with and had no luck getting either of the films made. One, I think you mentioned earlier, was a script called “On the Job,” which was my attempt at an Irish-American “Godfather,” set against the NYPD. You know, like a multi-generational Irish family epic that took place over the course of 15 or 20 years. Tried for years to get that made, could never get it made; stack of scripts, four or five different screenplays that had to do with the Irish mob on the west side of Manhattan. I wrote a turn-of-the-century story, I did an adaptation with William Kennedy of his novel “Legs.” I did a 1970s, kind of Westy’s gangster story, and I could never get any of these films made.

So when I went home to New York to think of what show I’d want to do, I thought why don’t I take these two passion projects of mine and marry the two ideas. That’s how I came upon this idea of, you know, the Muldoons, this extended NYPD Irish-American family from Hell’s Kitchen, and the Pattons will be the gangster family from Hell’s Kitchen. And they will be connected through the neighborhood, through similar experiences, and then they’ll also be connected through marriage. And that’s kind of where I started.

What was it that helped you with the transition from film to TV, and what was that process like for you?

When I sat down to write the 10 episodes, I decided not to try and write the individual episodes one at a time — write Episode 1 and move onto Episode 2 — I approached more the way you’d write a novel. And I kinda had some sense of where the chapters might end. But I tried not to think of them as individual episodes. Let me just do one or two passes in novel form with chapter breaks; lay out the story that way, see how the story flows and how that might play out. Once I did that, I was able to go into those individual chapters and sort of fine-tune those and craft those into individual television episodes. What this afforded me to do was… Getting 10 hours to tell your story instead of 90 minutes or two hours on a feature film, you just have so much more time to tell people’s stories and play with more complex characters. Unlike what’s happening in film, the fact that this was television, I could play with people who felt a little more real dealing with real emotions and real situations. That was kind of the approach.

The one thing I had was, you know, Steven Spielberg’s an executive producer, and Steven and his team at Amblin Entertainment really helped me in getting my head around how you deal with act breaks within the episodes. That was something I was completely unfamiliar with, and, quite honestly, as I broke my novel, let’s say, down into 10 chapters, I really needed their assistance, saying “Oh, well at the end of the fourth act you should have it end on this scene rather than that scene.” And having Steven as a mentor in the TV scene is as good as it gets.

It’s interesting that you said how much time you had to get into characters, because it’s something I’ve heard before when people talk about moving from film to TV. But this show feels so immediate. It’s a very tight, effectively-paced script, which isn’t usually the case for some people who make the transition. Outside of Spielberg’s influence, did you have anything you modeled the show after, like another TV show that inspired you or maybe a specific one of these stories from your past that felt like a way to access specific TV beats?

I would say there are two things I was looking at as I was writing the 10 episodes. One is a ton of Scorsese, and that’s probably evidenced in the style in which we shot the show. One of the things that the Scorsese [films have] — especially the gangster films — that a lot of other gangster stories don’t have, is the playfulness. The good time. And that’s something I knew I wanted my characters to have. Both the cops and the gangsters. I did not want it to drown in “heavy-osity.” I wanted it to feel like… even though these are bad guys, they’re having a good time. I think that what you said about it having a good pace or it being engaging, I think that might have something to do with it.

The other thing was, quite honestly, “Game of Thrones.” What I loved about “Game of Thrones” was that it was such an effective ensemble piece. You could jump around with all these different stories that at first don’t appear connected and wouldn’t necessarily dovetail until Season 2. So that would be sort of the more ensemble nature of the show. I definitely looked at “Game of Thrones” as inspiration for that. And since you’ve seen the first four episodes, you know we kill off some characters that probably five years ago we wouldn’t have been allowed to kill off. When I saw the end of Season 1 when they killed Ed Stark, I said, “Wait a second, you can do that? Okay, cool. I’m gonna start whacking some guys.” And that’s what we did.

You’ve been at the forefront of new distribution models as far as indie film goes for a long time now, and I was curious if that kind of understanding of how people are watching things these days affected your decision to get into TV.

Absolutely. It’s the natural progression for any indie filmmaker. We did back in ‘07 with “Purple Violets,” and putting that onto iTunes exclusively. That is where that indie-film-loving audience that used to go to the art house [goes]. They are now home in front of their televisions. This is really a case of where is the best place to tell this story. A friend of mine had a great line the other day, he told me “When we were kids, films were for adults and television was for children. And now the reverse is true.” And there actually is some truth to that. So for me, with this story, what I was able to do was… I could not ever have gotten this story made as a film. And if I did, it would have been very hard to reach a wide audience. And I think that’s why you’re seeing a lot of indie filmmakers making the decision to bail on the film career and embrace this new medium as the place to tell those stories.

We’ve definitely seen a huge movement in that direction.

For someone like yourself who’s so aware of the importance of distribution, what was it about TNT and their pitch that made that network the right fit for this show?

Two things. One is, I was working for TNT on the Frank Darabount show, and they approached me about coming up with an idea for a television show. So I only took this show to TNT. The thing that’s great about TNT is, Kevin Reilly, who runs the network, has talked about, you know, this is the direction that they want the network to go in. Telling these types of edgier stories, for lack of a better description. I think we’re sort of in the right place at the right time. We’ve got this story, and that’s where they want to take the network. They’ve been nothing but 100 percent supportive of us with everything. I mean, we got almost no notes while writing the script, no interference while shooting the episodes, and nothing but support during post-production. And even helping us to find a little bit more money so we can play even more music in the show.

So you’ve got a full season under your belt, you’ve got this great show coming out — where do you stand as an indie filmmaker? Can you see yourself going back to making more of those?

I’m sitting here right now at my desk, working on Episode 5 of Season 2, even though we haven’t been picked up yet. And I’ve got a stack of memoirs in front of me about cops and gangsters. So right now, the only thing I can think of is where do I take these characters; hopefully not just in Season 2, but Seasons 4 and 5. And as I said, this has been such a long labor of love trying to get a story like this to the screen. Back in ‘95, after “Brothers McMullen,” I thought that screen was going to be in a theater. But now, I am happier, actually, that it isn’t a film and that it is a television show. For all those reasons I said before. That said, if after the run of this show something hits me where I wanna make another film, I don’t wanna say no, but this has been such a charmed experience that I hope I get to do this for a long time. A big part of that is all of my department heads — all the people who worked on my indie films and all the people who worked on other folks’ indie films — it’s tough out there in the indie film world. Across the board, not only above the line but below the line, too, we’re all overjoyed that television has become the new home for these stories.

The cops in “Public Morals” aren’t presented as heroes or antiheroes, which is a fresh take in today’s TV landscape. And what struck me about that, considering the show’s title, “Public Morals,” was just what their relevance would be for a modern audience. Are they some kind of an old guard that’s been overwhelmed by P.C. culture, or are they a problem that existed and was washed away because of it?

I’m not quite sure what the question is, I’m sorry—

I’m sorry, let me rephrase: When I was watching these people go about their business — these are cops who are kind of on the take, working with people who are doing illegal activities throughout the city — they’re not presented as heroes or antiheroes. I’m just kind of curious what you thought of them, and what audiences are supposed to take away from these kinds of individuals?

I think, I mean, there was a division in the NYPD called Public Morals, and […] these crimes are sort of what they were in charge of policing. But in everything that I’ve read, going back to this book called “Island of Vice” about Teddy Roosevelt’s time as a police commissioner, there was this allowance made for what they call these “nuisance crimes,” or victimless crimes. I was fascinated that this culture and climate and way of doing business and making allowances had existed for a hundred years, back to Tammany Hall days. I don’t, and the show doesn’t, have any political agenda or any opinion as to whether it was right or wrong, These are really interesting characters for me to play with. I guess I was really just trying to sort of manipulate these stories and that history and play with questions of morality and power, but really also just try to make it a fun and entertaining piece.

“Public Morals” premieres Tuesday, August 25 at 10pm on TNT. The first four episodes will be available August 26 via watch.tntdrama.com, TNT’s mobile app and VOD. Watch the trailer below.

Edward Burns’ 1 Tip for Making Your Mark

Edward Burns’ résumé boasts an impressive list of filmmaker credits, but “Stoolie,” “No Sleep Till Brooklyn,” and “Rainy Dog” are not among them.

At first glance, they’re his failures—scripts about Irish-American cops and gangsters he couldn’t get made over the course of his 20-year career as a microbudget indie moviemaker. But as Burns gears up for his new TNT crime drama, “Public Morals,” it’s the abandoned ideas that are providing his greatest inspiration.

“I was always fascinated with Hell’s Kitchen and the Irish gangs and tough guys that sort of dominated that area for 100 years—just New York City folklore and all these archetypes: the tough-talking Irish cops, the Times Square hookers and junkies, the Italian wise guys, the Dead End Kids, the Bowery Boys, and those types of characters,” says Burns, who grew up the son of an Irish NYPD officer.

“My dad didn’t tell me a lot of stories about being a cop, but there were, like, five he told over the years,” the filmmaker says. “Sometimes when they would lock up hookers, if they knew they were going to night court and the girls were going to have a long night in a jail cell before being processed, they would take the girls out for sandwiches or a hamburger or something before bringing them down to book them.”

The anecdote stuck with Burns, and he wrote the scene into five screenplays that never got made. “When this show got greenlit, I was, like, ‘Of course I’m writing this scene into one of these episodes,’ ” he says.

Premiering Aug. 25, the 1960s-set “Public Morals” focuses on the NYPD as it tries to keep the peace when a war between two factions of the Irish Mob breaks out. “It’s a family saga and I dress it up like a gangster story, so I took two Irish-American families—the Muldoons, who represent the cops, and the Pattons, who represent the gangsters,” says Burns, who plays patriarch cop Terry Muldoon and is backed by a cast of veterans, including Brian Dennehy (“Death of a Salesman”) and Neal McDonough (“Justified,” “Suits”), and newcomers Aaron Dean Eisenberg and Keith Nobbs, among others.

After his arc on the 2013 drama “Mob City” ended, TNT approached him about developing a show for the network, and Burns jumped at the opportunity to tell this gangster-cop story he’d been dreaming up for years.

Backed by executive producer and friend Steven Spielberg, the writer-director-producer-actor was poised to experience a career high after struggling in “microbudget film land” for some time.

“I got to the place where I thought about throwing in the towel on the idea of being sort of an ‘indie auteur’ after a movie I made [in 2007] called ‘Purple Violets,’ ” says Burns, his third consecutive venture that “just didn’t work.”

The film was released solely on iTunes, and Burns’ next project, “Stoolie,” a Hell’s Kitchen gangster drama, never amounted to anything more than an idea. “We just could not get it made,” he says, flustered. “I mean, we knocked the budget down from $7 to $5 to $3 to $2.5 million and still couldn’t find anyone to cut a check. So I called my agents and I’m, like, ‘Maybe I should look at taking a director-for-hire gig,’ and basically just go direct a studio romantic comedy and get a paycheck.”

His agents were “over the moon,” but as a filmmaker who’d honed his own personal style for over a decade, Burns was reluctant.

“I thought, Do I really want to give up my dream? I’d spent whatever it was at that point—15, 16 years—pursuing a certain thing. Even if my thing was out of style, it was still my thing,” he admits. “I owned my tone, and if I went and did this I’d be giving that up. I was, like, What if Bruce Springsteen just all of a sudden decided, Well, no one’s into my stuff anymore so I’m going to hire some songwriters and do a pop album?”

The tone that Burns was unwilling to cast aside began taking shape with his first film, “The Brothers McMullen,” the 1995 Sundance Film Festival Grand Jury Prize winner about three Irish Catholic brothers on Long Island dealing with love, marriage, and infidelity—the success of which he attributes to “tenacity. I was 25 and didn’t know any better; I didn’t know the rules and didn’t know I was breaking them.”

Partnering with cameraman Dick Fisher, whom he’d met while working as a PA on “Entertainment Tonight,” the then-aspiring filmmaker put an ad in Backstage: “Low-budget film seeks nonunion actors. No pay but will feed,” with a description of the characters.

Burns, living in an illegal sublet at the time, set up the submissions to go to his parents’ house. “My dad calls me up, like, ‘What the hell is going on here? We just got, like, 500 headshots,’ ” he says, laughing.

Over the next two weeks, another 2,000 headshots arrived, two of which belonged to future “McMullen” cast members Connie Britton (“Nashville,”“Friday Night Lights”) and Michael McGlone (“She’s the One”)—friends the director would end up keeping throughout his professional career.

“Eddie is a very intelligent, a very literary, and a very charming filmmaker,” says McGlone. “He puts people at ease and you feel genuinely good in his company, which creates an environment that people want to thrive in.”

From the beginning, the actor says he knew “McMullen” was going to be something special because “you just don’t have that much happiness in a situation if it’s not blessed.”

Shot in 12 days over the course of eight months, according to Burns, the filmmaker “used available light. You piecemeal it together based on the availability of the actors you weren’t paying and the crew you weren’t paying,” he explains.

After being rejected by every film festival, a chance meeting with Robert Redford landed “McMullen” at Sundance, after which it secured distribution by Fox Searchlight and grossed $10 million nationwide.

Burns went on to make several films, including “The Fitzgerald Family Christmas,” “Newlyweds,” and 2010’s “Nice Guy Johnny,” which he calls “McMullen 2.0” because of its ultra low-budget production.

“[We spent] $25,000, three-man crew, unknown actors. Everyone had to do their own hair and makeup, the actors had to wear their own clothes, [and] we wouldn’t pay for a single location.” Putting these budget parameters on the projects, Burns says, helped him fall back in love with the process of making movies.

“Eddie’s ethics and his vision of what he wants as a director have always been very strong and very clear and that’s never wavered,” says Britton, who adds that she and Burns are “touchstones” for one another in a business in which it’s easy to forget your roots. “That was such a special and unique time during ‘The Brothers McMullen,’ so I think when we see each other now it’s a really lovely reminder of both where we came from and how fortunate we’ve been since then.”

Peppered with stories from his father and scenes that never made it into failed projects, “Public Morals” is Burns’ “shot”—a story he’s been fighting to tell for a long time, and an opportunity he might have lost if he’d taken a director-for-hire gig.

“The winds will change, but don’t change with them,” he says. “Stick to your thing. For an actor who wants to make his mark, he’s got to own his tone—whatever he feels he does well, whatever is authentic to him. Whatever your thing is, believe in it and just follow through on it.”

From ‘Public Morals’ to Spielberg’s ‘Spies’

Every working actor’s dream is to be cast in an Oscar-winning director’s newest film. Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, James Cameron—who wouldn’t relish an opportunity like that?

Well, stick with Burns and that dream could become a reality, as not one, but two actors cast in “Public Morals” now have parts in Spielberg’s upcoming historical thriller “Bridge of Spies,” starring Tom Hanks.

The “Schindler’s List” director took one look at Austin Stowell’s audition for the TNT drama and said, “We need to cast that kid; he’s a movie star,” according to Burns.

“We were very lucky to have Steven watching,” says Burns. “I mean, he would watch every audition of everyone who had even the tiniest little part and be like, ‘Where did you find that one? He’s incredible,’ ” he adds, in a spot-on Spielberg impression.

In addition to Stowell was Stephen Badalamenti—an actor in his 40s who recently quit his job in advertising to pursue his dream of performing. “He came in to play the Italian wise guy and he was just so good,” according to the filmmaker, that Spielberg cast him to do audio work in “Bridge of Spies.”

“Here’s this guy who, basically, wasn’t really a full-time actor, and Steven watches his audition tape and says, ‘I got a job for him,’”Burns says. “Makin’ dreams come true!”

To Hell and Back

Neatly stacked on a bookshelf in Ed Burns’s office in New York’s Tribeca neighborhood are some 20 unproduced film scripts he has written over the past two decades.

Buried within the trove of feature dramas with titles like Stoolie and Legs lies the multi-generational Irish-American Godfather-type saga On the Job, which he wrote in 1997 while starring in Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan.

It would be easy to miss these scripts within the room, part of a ninth-floor suite overlooking lower Manhattan. The eye naturally gravitates a few feet higher to a display of Burns’s stunning family, including photos of his wife, model Christy Turlington, snuggling their babies Grace and Finn, now eleven and eight, respectively.

But rather than sidestep the mountain of rejection that reflects the increasingly rigid studio-film marketplace, Burns is eager to introduce his other offspring.

“It’s another film we couldn’t get made,” says Burns, pointing to the Hell’s Kitchen gangster tale Stoolie. “That was the one point in my career where I was really tempted to throw in the towel because I thought I had a really great script, put together a great cast, but couldn’t get $2 million for it.”

But from futility sprang opportunity. All of these scripts, particularly On the Job, serve as the foundation for his TNT series, Public Morals, which begins its 10-episode first season August 25.

The story is set in the early 1960s and revolves around two Irish‑American families in Hell’s Kitchen, the Manhattan neighborhood once known for its tough rep and the poor Irish, Scottish and German immigrants who settled there in the mid–19th century.

In Public Morals, the Muldoons are the cops, and the Pattons are the gangsters. The title refers to New York City’s Public Morals Division, which investigates vice crimes; Burns plays Officer Terry Muldoon, and Michael Rapaport plays Charlie Bullman, his partner.

In 2013, Burns was coming off a stint as Bugsy Siegel on TNT’s short-lived drama Mob City when the network brass asked him if he had any interest in doing his own show. But as a writer-director, the native New Yorker worked almost exclusively in independent film, where he became a phenom after famously making The Brothers McMullen — a Sundance Grand Jury Prize winner — for $25,000.

He was skeptical but undeniably impressed with the latitude Mob City creator Frank Darabont had been given by the network.

“From a production standpoint, he’s got all the toys that any filmmaker would ever want to play with,” he explains.

“Any shot you could think of in your head, Frank could execute. The production value was just mind‑blowing. But the thing that really blew me away over the course of making the show was, I never saw any executives on set. He wasn’t getting any notes. He had total creative freedom. That opened my eyes. Maybe television is the place.”

But what story would Burns — who had spent much of his career exploring the mind of the commitment-phobic urbanite — be compelled to tell?

“I happened to glance up at all those unproduced scripts,” he recalls, “and I pulled them off the shelf. Everything I couldn’t get made was a Hell’s Kitchen–set gangster or cop movie. I said, ‘All right. That’s what the show’s gotta be.’”

Outside the offices that he bought in 1999 — before the price of real estate skyrocketed — Burns is talking animatedly with a nearby business owner. Ever the neighborhood guy, he spends so much time in Walker’s, the Irish pub next door, that he often has scripts and mail forwarded there.

In a white V-neck T-shirt, tan cargo pants and flip-flops, with sunglasses hanging from the V, he’s still exuding downtown cool all these years post–Brothers McMullen. But there’s more than a hint of the working-class boy who hails from an old Hell’s Kitchen family and grew up steeped in cop culture. Burns’s father and late uncle were cops, as are five first cousins and two childhood buddies.

“Back when he was making Private Ryan, Steven [Spielberg] met my uncle and my dad,” Burns says. “They told him a handful of great stories about what it was like to be a cop in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s. Steven said, ‘You gotta write a script about those guys. DreamWorks will hire you to write that script.’”

But as a film, On the Job never found traction, and Burns went on to give his acting career a shot with follow-up roles in studio films like 15 Minutes, opposite Robert De Niro, and Life or Something Like It with Angelina Jolie. All the while, he continued to write-direct-produce and star in micro-budget movies in the Brothers McMullen vein, like Looking for Kitty, Purple Violets and Nice Guy Johnny.

Not long after TNT asked for some ideas, Burns ran into Spielberg at a barbecue in the Hamptons.

He’s like, ‘What are you working on?’” Burns remembers. “I said, ‘It’s funny — it’s not so different from the script I wrote for you 19 years ago.’ And he’s like, ‘Why don’t we get involved?’”

Spielberg’s Amblin Television already had a hit on its hands with another period-set basic cable show, FX’s The Americans, and was well positioned to champion the project properly.

“That’s as good a scenario as you could ask for to pitch a television show — have Steven at the head of the table and basically say to the folks at TNT, ‘Hey guys, Eddie has this great idea. This is what it is….’”

Rather than simply pitch the idea, Burns presented his 45-page pilot script to avoid being “noted to death,” and TNT responded with an immediate yes.

He shot the pilot in January‑February 2014, and Public Morals was picked up to series three months later. In addition to creating the series, Burns wrote, directed and starred in every episode. Few in the TV landscape are as multifaceted, with some notable exceptions like Louis C.K.

“He has brought everything he has learned as an independent filmmaker to series TV production,” says Justin Falvey, an executive producer on Public Morals and co-president of Amblin Television (the other exec producers are Burns, Amblin chairman Spielberg, Amblin co-president Darryl Frank and Aaron Lubin, who has produced several of Burns’s features).

“People talk about the triple threat. Eddie’s the quadruple threat by throwing acting into the mix. Nobody else does it, particularly for a show of this scope. It’s an hour and a period piece. It is absolutely remarkable.”

Burns has no good explanation — other than his sole vice, coffee — for why he’s able to juggle so effectively. But he does point to parenthood as making him more efficient in all aspects of his life.

“Once you get married and have kids, all of the bullshit falls by the wayside,” says Burns, who lives around the corner from his office in a loft once owned by JFK, Jr. “As a guy in my 20s, I drank a lot. But I don’t party anymore. I just work much harder now than I did before I was married with kids. Being bored isn’t something that I’ve experienced in 11 years. Being tired, yes, but never bored.”

But Public Morals star Neal McDonough, who has five children of his own, argues that Burns is more akin to a superhero than a mere multi-tasking mortal.

“He never gets flustered, never gets upset and is always energetic,” marvels McDonough, who plays mobster Rusty Patton.

“He can write all those episodes, direct all those episodes and star in all those episodes and still make it to his kids’ basketball practices or ballet recitals at five o’clock in the afternoon. With eight-page days, we’d finish in 10 hours. For a lot of TV shows, it’s not uncommon to have four-page days and finish in 16, 17 hours. But he knew exactly what he wanted as a director. And for that, the cast and crew loved him.”

In fact, many who enter Burns’s professional vortex stay there. Casting directors Laura Rosenthal and Maribeth Fox have worked with Burns on every project since his second movie, She’s the One.

And for Burns’s 35 birthday, Turlington bought him a guitar and guitar lessons from a then-21-year-old musician named P.T. Walkley, who has since become Burns’s go-to composer. Walkley created the score for Public Morals.

Nashville star Connie Britton has collaborated with Burns five times, including on Brothers McMullen, a role she landed when she was a struggling actress-aerobics instructor after answering an ad in Backstage.

“I could get emotional talking about Eddie because I literally owe my entire career to him. Period,” Britton says. “He is someone who is somehow able to walk the line between manifesting his vision and being completely open to collaboration with the people he has carefully chosen to support him.”

Actress Kerry Bishé, who has worked with Burns on Nice Guy Johnny, Newlyweds and The Fitzgerald Family Christmas, carved out time from her busy schedule as a star on AMC’s Halt and Catch Fire to appear in two episodes of Public Morals.

“As a director, he’s got a deep respect for actors and their ideas and really solicits their input, and that’s rare,” she says. “And as an actor, I love that he’s not precious. He’s a really practical actor. He’s got his focus in the right place and he knows the right way to think about the scene. I think his priorities are in the right place.”

One of Burns’s top priorities with Public Morals was creating a world that accurately portrayed the cop-and-criminal dynamic of the era.

He could find no better resource than his father, Edward J. Burns, who started in the 25th Precinct as a rookie cop and eventually became the NYPD spokesperson in the Office of Public Information. There were often surreal moments for the young Burns, like hearing his father deliver the news to the world that John Lennon had been shot and killed in front of his home.

Long since retired, the elder Burns now serves as a consultant on the series.

“When he read the first draft, he was like, ‘It’s a good story, but your dialogue is terrible. We didn’t talk like that. Like, you don’t call it a badge in the NYPD. You call it your shield,’” Burns relates. “You can’t get that in a book.”

Nor can one get in a book the firsthand knowledge Burns gleaned as the son of a cop. Living in Valley Stream, Long Island, the family would trek into the city for theater outings and be treated to atypical sights. “We would drive around, and he would take us through certain neighborhoods to look at the gangsters. ‘Look at the hookers,’ he would say.” Burns laughs at the memory.

It’s no surprise that Burns’s younger brother Brian, a longtime writer on Entourage, also dips from the same well as an executive producer on CBS’s Blue Bloods. “We didn’t become cops, but the NYPD is keeping us employed,” Burns jokes.

Amblin’s Darryl Frank says it’s that personal connection to the material that elevates Public Morals. “He’s the divining rod on what feels authentic in this world, and how this story should and needs to be told.”

Back on the Public Morals set, Burns is shooting a scene with McDonough, who is about to dismantle the neck of an adversary. Spielberg is huddling on the sidelines, watching the action on a crisp Manhattan day. He’s drinking in the by-product of a story hatched nearly two decades ago, when Burns was his young acolyte.

“Watching Steven be kind of mesmerized and amazed by how Ed works on a set, I could see how happy Ed was,” McDonough recalls later. “Steven is the king of kings, and when you have that guy looking at you with a thumbs-up and that kind of adoration — that was pretty awesome.”

Ed Burns on the Phone Call With Steven Spielberg That Lead to TNT’s ‘Public Morals’

Ed Burns is a native son to independent filmmaking, but soon he’ll be a player in the cable prestige drama game with TNT’s “Public Morals.” As it turns out, the project came together with the help of an old friend — Steven Spielberg.

The upcoming drama was partially adapted from a police screenplay Burns had written for DreamWorks after the men filmed 1998’s Oscar-winning “Saving Private Ryan.”

“I called up Steven and said, ‘I’m doing this thing for TNT. I know how much you loved the old cop script, I’ve kind of reimagined it a bit. Would you mind taking a look?’ Since ‘Private Ryan’ he’s been a bit of a mentor to me,” Burns told TheWrap.

“He called back and said, ‘I love this Eddie, I’d like to get involved, let’s help get this made,” Burns said.

Burns is creator, director and star of the show executive produced by Spielberg, about a police unit that serves as a skewed moral compass in Hell’s Kitchen, New York in the ’60s. Inspired by the DreamWorks script and additional projects Burns had written over the years, he said the guidance of Spielberg made the process a “charmed experience.”

The result is a sleek, violent tale co-starring Neal McDonough, Elizabeth Masucci, Michael Rappaport, Ruben Santiago-Hudson and Austin Stowell.

Burns faced an interesting challenge in making the series — having too much money to execute his vision.

“It took me a couple of episodes to finally take off the indie filmmaker coat and realize, ‘I do have the time to go for that shot, that location, to dress it — I can have 200 extras in period clothes! In period hair and makeup!’” he said.

“I had to get comfortable not always being hat in hand. It felt great, I hope I never have to go back.”

Burns is already engaged writing the second season, but as he tells it, his 9-year-old son Finn is demanding a more modern project on his hiatus.

“Basically, every time my son watches a new Marvel movie he says, ‘Dad, when are you going to do something cool like that?’” Burns said.

And would he slip into the spandex of his peers Chris Hemsworth, Anthony Mackie or Jeremy Renner?

“Absolutely. I would love to do a superhero movie,” he said.

“Public Morals’ premieres August 25 on TNT.

Ed Burns’ new cop drama hits close to home

Ed Burns wasn’t supposed to direct all 10 episodes of his new TNT cop drama “Public Morals,” but he took over during the fourth episode for a scene featuring cops arresting hookers in the ’60s — because his dad, a former police officer, used to do the same.

“Public Morals” centers around Hell’s Kitchen cops and gangsters, inspired by stories from Burns’ father and uncle, both retired NYPD cops. Burns’ dad once revealed that he and others used to take the call girls out for a bite after their arrest.

“The girls never resisted arrest because they knew they would just be taken down to court and in an hour’s time be back on the street,” filmmaker Burns told Hamptons magazine. So the cops would sometimes take the women for food before they went to the precinct.

“I loved this idea that the cops and these hookers would go out and get a couple of hot dogs together before getting processed. When we were in pre-production . . . I was just jealous that I wasn’t going to direct the scene because I had written a version of it 18 years ago, and put three different versions of that scene in three different screenplays.”

But Burns took over direction for that scene and the rest of the series, executive-produced by Steven Spielberg, which debuts on Aug. 25.

Turner Jumps On Binge Bandwagon, Will Release ‘Public Morals’ Episodes On-Demand First

Turner Broadcasting System is the latest linear TV company to join the trend of releasing multiple episodes of a series simultaneously, a model introduced by streaming platform Netflix.

For the first time, TNT will make multiple upcoming episodes of a series available on-demand. The day after the Aug. 25 premiere of the Edward Burns period drama Public Morals, episodes 1-4 will be viewable through set-top VOD, the Watch TNT mobile app and http://www.tntdrama.com/watch, as well as on participating TV providers websites and apps. Sibling truTV will do the same with new series Friends of the People, whose first two episodes will be available on-demand before their premiere.

NBC recently became the first traditional network to release an entire season of a show on-demand with summer drama Aquarius.

Additionally, TNT will make every episode of the reality investigative series Cold Justice available on demand to leading into the season 3 finale on Sept. 18. That includes the entire Seasons 1 and 2. Additionally, episodes currently airing from season 3, which premiered on July 31, are made available on demand the day after their TV debut and will stay up through the finale.

truTV will offer their every single episode of Impractical Jokers – seasons 1 through 3 – on demand beginning this week, leading into Jokers Week and the Impractical Jokers Live Punishment Special celebrating the 100th episode on Sept. 3. In what Turner calls an unprecedented move, the network will make every single regular-season episode to date, as well as Impractical Jokersspecials, available via VOD and digital on-demand to truTV subscribers. Additionally, starting on August 5, truTV will offer fans a sneak peek of two brand new episodes of Friends of the People before their TV premiere.

“Turner is embracing a different approach to the way programming is traditionally released and providing our audiences with multiple binge-viewing options in order to enhance their TV experience,” said John Harran, SVP of business & product development at Turner Content Distribution.

On A Hot Streak: Edward Burns Co-Chairs Authors Night, ‘Public Morals’ In The Wings

Edward Burns could once mow a mean lawn.

During his summer breaks from college, his talents brought him to the East End, where he bused tables, cleaned swimming pools and, most memorably, landscaped the front yard of author Joseph Heller, who had converted his garage into a writer’s studio in Amagansett.

The men never spoke, Mr. Burns recalled last week during a telephone interview. But as he pushed his mower past that small room, he made a mental note, keeping one eye on the literary giant and the other on the half-cut grass: If he ever made enough money, he would live not far from here, writing in his own summer studio every day he pleased.

Since 1995—following the success of his film, “The Brothers McMullen”—Mr. Burns has done just that.

First, it was his kitchen in a Wainscott rental, then his home on Gerard Drive in Springs, and, finally, a screened-in porch at his house in East Hampton. There, last summer, he penned the entire first season of his police drama “Public Morals,” premiering Tuesday, August 25, on TNT—not to mention a part-memoir, part-textbook, “Independent Ed: Inside a Career of Big Dreams, Little Movies, and the Twelve Best Days of My Life,” over the course of several years, with the help of journalist Todd Gold.

The book has landed him a seat among 100 participating writers at Authors Night on Saturday in East Hampton, where he will co-chair the mass signing event alongside Robert A. Caro, Dick Cavett, Tom Clavin, Nelson DeMille, Christina Baker Kline and Lynn Sherr, as well as founders Alec Baldwin and Barbara Goldsmith.

He has his wife, supermodel and fellow author Christy Turlington, to thank for that.

“She had said, ‘You keep trying all these different things during your indie film career—you ought to think about writing a book, a how-to guide but also a cautionary tale,’” Mr. Burns recalled. “I thought it was a great idea, but, quite honestly, I did not have the time.”

The year was 2007. Mr. Burns was already looking ahead toward his next project, after releasing his film “Purple Violets” via iTunes—the first of its kind to go exclusively digital, he said.

“When we did press for that, 80 percent of the journalists said, ‘You’re crazy—people are never going to watch movies on their computers,’” he said, a smirk nearly audible through the phone. “It was a time when the writing was on the wall for indie filmmakers, that the golden age was coming to a close. The art house theaters around the country were closing, and people were no longer selling their indie movies at Sundance for millions and millions of dollars.”

It was a vastly different climate from the film world he grew to love in the 1980s, even though the Valley Stream native had always planned to be the next great American novelist—a fleeting dream, he realized, when he landed himself on academic probation at SUNY Albany in the fall of 1987. “I was not a great student,” Mr. Burns admitted. “My advisor called me and said, ‘Look, you have to get your GPA up. If you take a film studies class, watch old movies and write a paper on it, it’s a guaranteed easy A.’ I said, ‘Okay, I’m in.’”

The first film the professor screened was the 1960 comedy “The Apartment,” and Mr. Burns was so captivated that he had a revelation: Forget novels—he wanted to write movies. He took every film class the university offered and, just in time for his senior year, transferred to Hunter College’s film department.

One day in between classes, Mr. Burns was walking up Sixth Avenue and saw director Spike Lee ahead. He had countless questions for the director, he said, but couldn’t work up the nerve to approach him. In the years since, they have crossed paths—Mr. Burns is sure he recounted the story during one of their early meets—and it is a memory Mr. Burns always keeps in mind while addressing his fans and film students, whether its via Twitter or in a classroom setting.

After making a series of back-to-back micro-budget films —“Nice Guy Johnny” in 2010, “Newlyweds” in 2011, and “The Fitzgerald Family Christmas” in 2012—he set out on a publicity campaign, hitting every film festival, film society and film school that would have him.

“I have successes, and I’ve made some very costly mistakes and I’ve fallen on my face. I had all these lessons to pass on to young filmmakers,” he said. “A number of professors would say, ‘These are great stories—have you ever thought about writing a book?’ Every time I’d mention it to Christy, she’d say, ‘Yeah, I’ve been telling you that for years!’”

He laughed, and continued, “The credit has to go to Christy. She nudged me in that direction. She’s very happy with herself.”

This summer, Mr. Burns is back on his screened-in porch, working on season two of “Public Morals.” He writes every day on his laptop, a process that is never painful—though that is true only of writing fiction, he said.

“I have to admit, writing screenplays is a lot more fun, because you can lose yourself in a screenplay,” he said. “Having to go in and do multiple drafts on this book felt more like a homework assignment. I have no interest in writing another one. I’ll stick to the scripts.”

The 11th annual East Hampton Library Authors Night will be held on Saturday, beginning at 5 p.m., at 4 Maidstone Lane in East Hampton. Tickets are $100 and may be purchased at the gate. Author dinners will follow at various locations; tickets start at $300. For more information, call (631) 324-0222, ext. 7, or visit authorsnight.org.

TNT’s fine ‘Public Morals’ sets itself apart from cop dramas

“Public Morals” is proof that even in this time of television’s Great Overcrowding, one should never judge a show by its genre.

In theory, Edward Burns’ tale of cops ‘n’ gangsters mingling and mangling on the mean streets of circa-1960 New York is the last thing we need. Add a zombie menace and/or a female character Fighting to Be Taken Seriously, and you have a show so close to modern drama du jour it risks becoming parody.

Except it doesn’t, not at all. “Public Morals,” which premieres Tuesday on TNT, is a picaresque, briskly written and quickly captivating series that is neither afraid nor ashamed of entertaining its audience. Though it deals with its genre’s big issues (the difference between law and order, the danger of defining oneself through loyalty), “Public Morals” does not fall prey to the current epidemic of Televisionous Prestiguous (symptoms may include swollen monologues, lethargy and sensitivity to normal light).

Instead, with a touch so light it defies gravity , Burns simply tells a story that he knows — his father was a New York cop — in the way of storytellers he admires. Martin Scorsese is, of course, fully accounted for in careful choreography of sudden violence and hierarchy of menace; the calmest, most gracious character, in this case a mob boss played by Brian Dennehy, is always the most dangerous. The influences of Steven Spielberg, who serves as executive producer, also make themselves felt in the scenes of family dinner and parent conferences with the nuns, in the newsboy caps of street kids who say things like “I ain’t got no muddah.”

But the fulcrum is all Burns, who created, writes and stars as Terry Muldoon, the unofficial organizer of the NYPD’s Public Morals Division, a team defined by its relationship to the city’s Underworld.

Handsome, genial, devoted to family and friends, Muldoon is, of course, on the take. As he explains to clean-cut newcomer Jimmy (Brian Wiles), who might just be a rat, most of the jurisdiction Public Morals covers is ridiculous. Does any real cop think he’s going to end prostitution by busting a couple of hookers and their johns? Does anyone really care if a few “queers want to play grab-ass” or if people like to gamble their money away in high-stakes games?

No, of course not. But the city needs to remain peaceful. Public Morals is there not to eradicate this type of crime but to manage it. “Think of us as landlords,” Muldoon says. “If you want to do business, you have to pay the rent.”

He and his less-talk-more-action partner Charlie (the always excellent Michael Rapaport) make it all look so easy. When he isn’t lecturing a john, from whom he just took a bribe, to leave New York hookers alone, Muldoon’s letting his son know that sassing Sister is the first step on the road to the wrong side of the street.

With his wise-guy squint and husky tenor, Burns sells the sincerity of his character if not his world view. This is not a broken hero, but a practical one. In another set of circumstances, Muldoon could be a politician, or a mob boss.

That is, of course, the point, as it almost always is in stories about lawmen and lawbeakers. That line is so darn thin, especially in a place like this version of Hell’s Kitchen, which, with its mostly Irish population, is so insular that Muldoon’s uncle, Mr. O (Timothy Hutton) is the local numbers man as well as the father of Sean (Austin Stowell), a member of Muldoon’s team.

And, indeed, Mr. O is about to set off a series of events that destroys the calm that Muldoon and his crew have maintained for so long. New players are on the scene, with big ambitions and little deference to the old codes.

Mercifully, Burns is in no rush to hit a hard-R rating or prove some big point about the changing state of the nation. The show may lean digital in distribution — the first four of 10 episodes will be available online after Tuesday night’s premiere — but the narrative unfolds the old-fashioned way, with multi-layer stories full of, but never overwhelmed by, colorful characters, archetypal themes and small odes to genre.

Muldoon is in constant but loving battle with his wife over parenting techniques and her desire to move to the suburbs, Charlie becomes the protector of a young prostitute, and everyone tries to figure out whether Jimmy can be trusted. On the other side of the law, prodigal son Rusty (Neal McDonough) has returned to his aging father/crime boss Joe Patton (Dennehy) with predictably incendiary results.

It all flows swiftly across the screen in oversized taxis and a chorus line of shot glasses and beer bottles, propelled by a men-wearing-hats syncopation that nods to the films of James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson but doesn’t kowtow.

Out of memory, myth and the inevitable allure of mayhem, “Public Morals” creates its own cinematic world, as inbred and self-curated as the most lived-in, teeming New York neighborhood and just as much fun to visit.

“Public Morals” Premieres Tonight!

Public Morals premieres tonight, Tuesday, August 25, at 10/9c only on TNT.

Watch a Behind the Scenes clip here:

Recent Articles:

Edward Burns is arresting in ‘Public Morals’ – USA Today

Ed Burns’ real-life cop father inspired his new police drama – New York Post

Edward Burns’ 1 Tip for Making Your Mark – Backstage

More “Public Morals” Press

Public Morals premieres Tuesday, August 25, at 10/9c only on TNT.

Look out for Edward Burns on ‘Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon’ tonight, Tuesday, August 18. Check your local listings.

Check out some additional recent press:

Ed Burns on the Phone Call With Steven Spielberg That Lead to TNT’s ‘Public Morals’ – The Wrap

‘Public Morals’ star Edward Burns finally brings his passion project to life – HitFix

More on “Public Morals”

Public Morals premieres Tuesday, August 25, at 10/9c only on TNT.

Look out for Edward Burns on ‘Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon’ tomorrow, Tuesday, August 18. Check your local listings.

Check out some recent press:

To Hell and Back – Emmys.com

An Illustrated Guide to New York City’s Modern Vices – Vulture

On A Hot Streak: Edward Burns Co-Chairs Authors Night, ‘Public Morals’ In The Wings – 27east

Turner Jumps On Binge Bandwagon, Will Release ‘Public Morals’ Episodes On-Demand First – Deadline

Ed Burns’ new cop drama hits close to home – Page 6

Unearthing signs of the ’60s in New York – The Bulletin

Ed Burns and his filmmaking dream come true – CBS Sunday Morning

“Public Morals” Featured in ‘Newsday’

Fast chat: Edward Burns on his new TNT series, ‘Public Morals’ – Newsday

Public Morals premieres Tuesday, August 25, at 10/9c only on TNT.

“Public Morals” Featured In ‘Variety’

Edward Burns Celebrates TNT’s ‘Public Morals’ After 18 Years in the Making – Variety

Public Morals premieres Tuesday, August 25, at 10/9c only on TNT.

“Public Morals” Press

Public Morals premieres Tuesday, August 25, at 10/9c only on TNT.

Check out some recent press:

For ‘Public Morals,’ Edward Burns Exhumes the ’60s From Manhattan Streets – The New York Times

A Watershed Year for Edward Burns – The East Hampton Star

Interview: Edward Burns writes what he knows (and loves) in TNT’s Public Morals – Channel Guide Magazine